- The E'ville Good

- Posts

- Bridging Cultural Divides: How Understanding Communication Styles Can Heal Community Polarization in Rural Minnesota

Bridging Cultural Divides: How Understanding Communication Styles Can Heal Community Polarization in Rural Minnesota

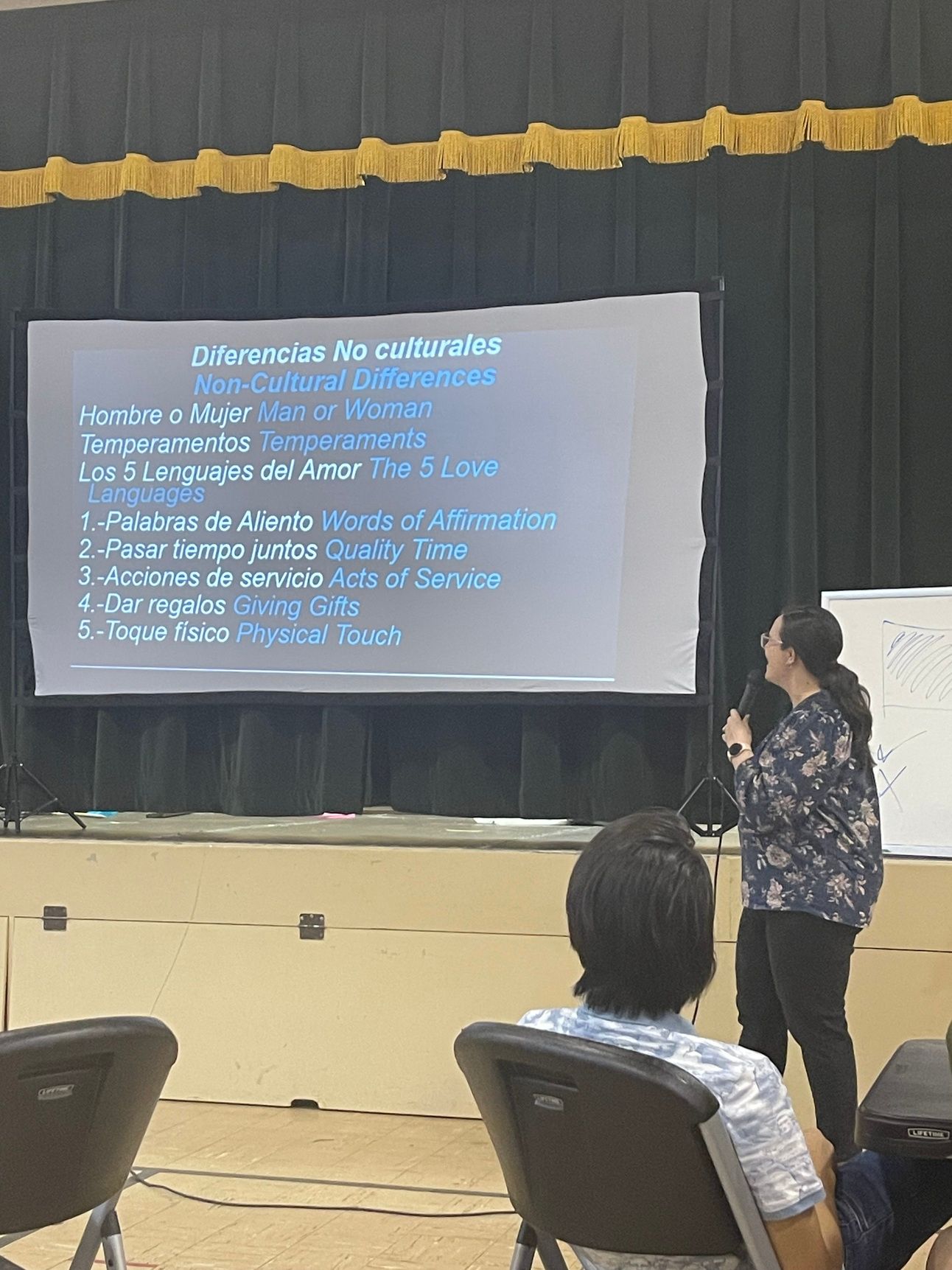

Based on insights from a cross-cultural communication workshop presented by Lucio and Vanita sponsored by Jackson Center for the Arts

Introduction

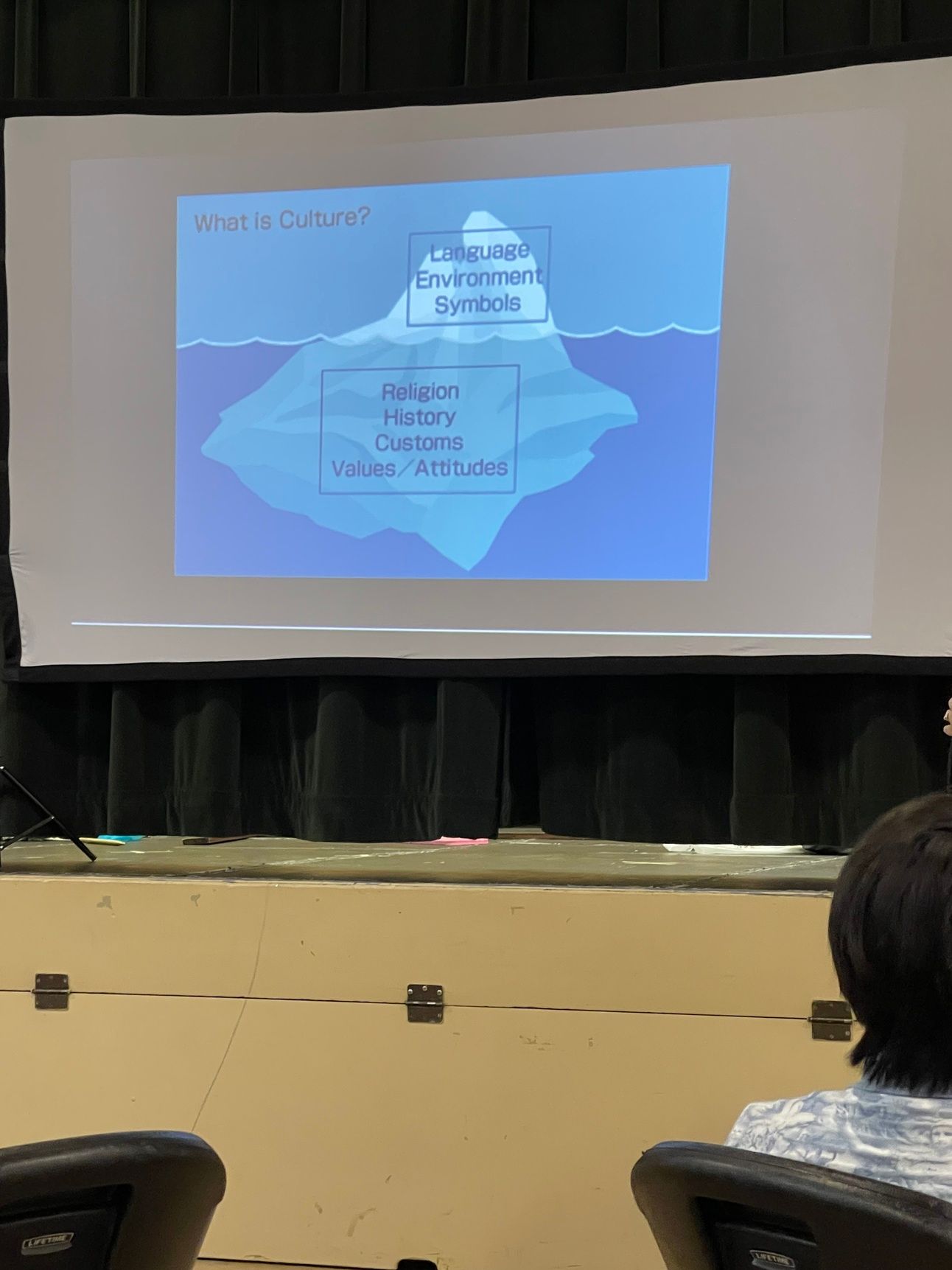

In the small communities of southwestern Minnesota, cultural misunderstandings often create invisible barriers between neighbors. What appears as rudeness, laziness, or disrespect may actually be deeply ingrained cultural differences in communication and social interaction. A recent workshop on cross-cultural communication revealed how these misunderstandings contribute to community polarization—and more importantly, how awareness can bridge these divides.

The 80/20 Rule: Understanding Cultural Tendencies

The workshop introduced the concept that no culture is 100% uniform. Using the “80/20 rule,” presenters explained that while 80% of a culture may lean toward certain behaviors, 20% will differ. This nuanced understanding helps avoid stereotyping while recognizing genuine cultural patterns.

For rural Minnesota communities, this means acknowledging that both “warm culture” (relationship-oriented) and “cold culture” (task-oriented) approaches exist within the same geographic area, often creating tension when expectations don’t align.

Two Fundamental Cultural Orientations Relationship-Oriented vs. Task-Oriented Cultures Warm/Relationship-Oriented Cultures prioritize: •

Building personal connections before conducting business

• Greeting everyone individually, even when arriving late

• Taking time for small talk and relationship maintenance

• Making decisions based on feelings and group harmony

• Viewing lateness as less concerning than relationship preservation

Cold/Task-Oriented Cultures emphasize:

• Efficiency and time management

• Getting work done before socializing

• Respecting others’ time through punctuality

• Making logical, systematic decisions

• Separating personal relationships from professional tasks

Communication Styles:

Direct vs. Indirect Direct Communication (Cold Culture)

• Clear, precise, and professional language

• Ability to separate critique of work from personal relationships

• “Yes means yes, no means no” with no hidden meanings

• Efficient problem-solving focused on facts

Indirect Communication (Warm Culture)

• Lengthy context-setting before making requests

• Concern about preserving feelings and avoiding offense

• Use of stories and relationship-building in professional settings

• Difficulty separating personal identity from work or actions

Real-World Examples of Cultural Collision: The Parent-Teacher Conference

Lucio shared his experience arriving at his child’s school conference, attempting to build rapport with the teacher through personal questions. The teacher, operating from a task-oriented framework with limited time slots, perceived this as inconsiderate.

Lucio, following his cultural norm of relationship-building, felt dismissed when told his child needed to use an “indoor voice.”

The Workplace Misunderstanding

Another example involved a neighbor who declined a social invitation simply by saying “I need to read.” The indirect-communication interpreter heard rejection and built walls, while the direct communicator meant exactly what they said—they had studying to do for a graduate program.

The Geographic and Economic Factors The workshop highlighted how climate and economic conditions shape cultural orientations:

• Cold climates require task-oriented preparation for seasonal challenges

• Warm climates allow for more event-oriented, flexible scheduling

• Wealth disparity affects relationship dependence—lower-income communities rely more heavily on shared resources and social connections

• Agricultural communities develop task-orientation due to weather-dependent, time-sensitive work

Breaking Down Stereotypes and Building Understanding Moving Beyond Surface-Level Judgments When warm-culture individuals see cold-culture efficiency, they may perceive:

• Rudeness or lack of caring

• Unwillingness to build relationships

• Coldness or superiority

When cold-culture individuals encounter warm-culture approaches, they may perceive:

• Inefficiency and time-wasting

• Lack of professionalism

• Disorganization or laziness

The Path to Mutual Understanding

The workshop emphasized that neither approach is wrong—they’re simply different cultural adaptations. Recognition of these differences allows community members to:

1. Give others the benefit of the doubt rather than assuming negative intentions

2. Adjust communication styles when interacting across cultural lines

3. Recognize their own cultural lens and how it shapes perceptions

4. Build bridges by understanding what motivates different approaches

Practical Applications for Rural Communities For Community Leaders

• Design inclusive meeting formats that accommodate both relationship-building and task completion

• Allow time for both direct and indirect communication styles

• Recognize that punctuality preferences vary across cultural backgrounds

• Create space for both individual and group decision-making processes

For Community Members

• When someone seems “rude,” consider they may be operating from a direct-communication culture

• When someone seems “inefficient,” recognize they may prioritize relationship preservation

• Practice cultural code-switching—adapting your communication style to match the situation

• Ask clarifying questions rather than making assumptions about intent

The Role of Awareness in Reducing Polarization

Understanding cultural differences provides a framework for depolarization by:

Replacing Judgment with Curiosity: Instead of viewing different approaches as character flaws, community members can recognize them as cultural adaptations.

Creating Shared Vocabulary: Terms like “warm culture” and “cold culture” give people language to discuss differences without blame.

Building Empathy: Understanding the logic behind different cultural approaches helps people see good intentions even in unfamiliar behaviors.

Encouraging Flexibility: Awareness allows people to adapt their communication style for better cross-cultural understanding.

Conclusion: Building Belonging Through Understanding

Rural Minnesota communities benefit greatly from this cultural competency framework. When a Latino pastor feels dismissed by efficient meeting styles, or when Norwegian-heritage farmers perceive relationship-building as time-wasting, the real issue isn’t personal incompatibility—it’s cultural miscommunication.

By developing awareness of these patterns, small communities can transform potential sources of division into opportunities for deeper understanding. The goal isn’t to eliminate cultural differences but to create space where multiple approaches can coexist and complement each other.

As the workshop demonstrated, the pathway to community belonging runs through mutual understanding. When we recognize that our neighbors’ “strange” behaviors often reflect deeply ingrained cultural wisdom adapted to different circumstances, we can move from judgment to appreciation, from polarization to integration.

The strength of rural Minnesota communities lies not in cultural uniformity, but in their capacity to honor different approaches while working toward common goals. Understanding cross-cultural communication provides the tools to build that strength, one conversation at a time. This framework offers hope for communities struggling with polarization: often, what divides us isn’t fundamental disagreement about values, but simply different cultural approaches to expressing those shared values. Recognition and respect for these differences can transform sources of conflict into sources of community resilience.